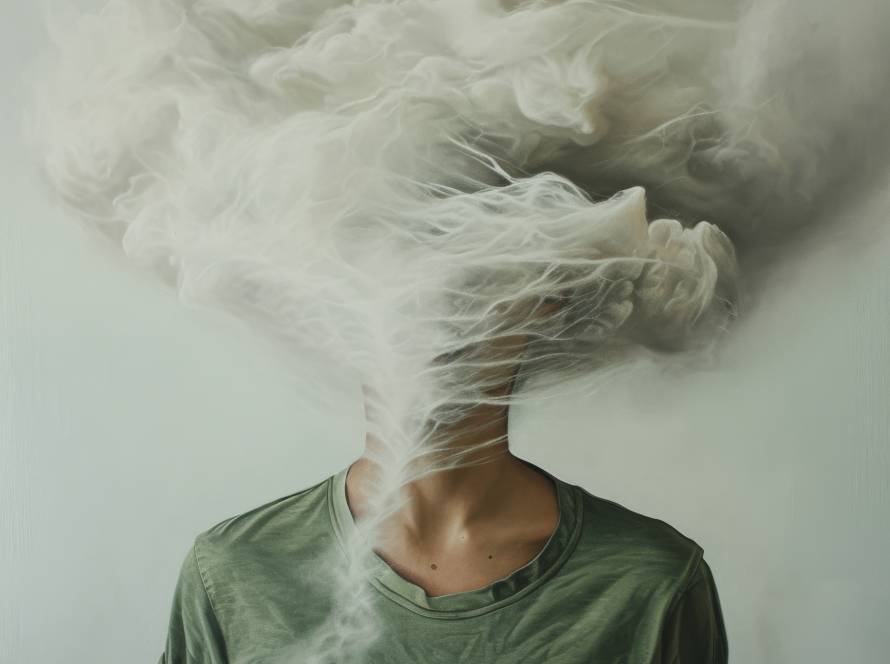

The Impact of Trauma

Trauma, an experience that profoundly affects an individual's life, can manifest in various forms, leaving an enduring impact on one's physical, emotional, and psychological well-being. It is often associated with life-threatening events like accidents, natural disasters, or violence. However, trauma can also stem from seemingly less dangerous but equally devastating experiences such as ongoing emotional abuse, being held hostage and rendered helpless in threatening situations, bullying, harassment, or witnessing traumatic events. A person subjected to constant threats, bullying, or harassment lives in a state of perpetual fear, pressure, and emotional pain. Being constantly on edge and in fear can lead to feelings of helplessness, entrapment, and loss of control, creating traumatic effects much like physical violence.

Trauma can lead to various psychological outcomes, including anxiety, depression, difficulty in emotional regulation, and a persistent sense of insecurity. Constant fear and anxiety can result in a state of hypervigilance, making it difficult for the individual to feel comfortable and relaxed in their surroundings. Additionally, trauma can damage one's ability to trust others, making it challenging to form secure attachments and maintain healthy relationships.

The Problem of Evil and the Social Dynamics of Trauma

As Judith Herman points out in Trauma and Recovery, the study of trauma itself has a curious history—one of " episodic amnesia", where hard-won insights are repeatedly buried and forgotten, only to be laboriously rediscovered years later (Herman, 1992). This is not simply a matter of changing intellectual trends, but rather a consequence of the intense controversy and fundamental questions of belief that the subject provokes. Herman talks about the societal dynamics that often enable trauma and hinder recovery. She argues that studying trauma forces us to confront both human vulnerability and "the capacity for evil in human nature." (p. 7).

When trauma is caused by humans, it raises difficult questions about responsibility, morality, and the very nature of reality. As Herman (1992) explains, "When the traumatic events are of human design, those who bear witness are caught in the conflict between victim and perpetrator. It is morally impossible to remain neutral in this conflict. The bystander is forced to take sides." (p. 7). Yet, siding with the victim requires acknowledging the reality of the trauma, sharing the burden of pain, and demanding action and accountability. This can be deeply unsettling, challenging our assumptions about safety and justice. This often leads to denial and minimization of the trauma, as it is easier to side with the perpetrator and maintain the illusion of a safe and just world.

The human mind tends to reject evils that go beyond its comprehension. This denial creates an environment of disbelief and resistance, which allows horrific events to thrive. As a defense mechanism on both a societal and individual level, this denial stems from the desire to avoid confronting an unbearable reality. The Holocaust is one of the most striking examples of this phenomenon in history. When the atrocities of the Holocaust were revealed, much of the world struggled to accept the reality of such systematic brutality for an extended period. The difficulty in grappling with this reality underscores humanity’s profound vulnerability in the face of evil. Because horrific events often take place in secrecy, hidden from a world that chooses not to believe, evil flourishes in this darkness. Perpetrators rely on this denial to continue their actions. Until people confront the reality of such events, their own optimism or naivete can unknowingly create space for these horrors to occur. The denial and minimization of trauma allow individuals and societies to cling to the illusion that "bad things don't really happen." However, this denial feeds the negative cycle created by trauma and leaves victims feeling isolated and helpless.

This erosion of trust is further compounded by societal responses that often silence and discredit victims. Herman highlights the perpetrator's reliance on secrecy and silence to escape accountability: "In order to escape accountability for his crimes, the perpetrator does everything in his power to promote forgetting. Secrecy and silence are the perpetrator’s first line of defense." (Herman, 1992, p. 8). If secrecy fails, the perpetrator will often attack the victim's credibility, using a range of arguments to deny, rationalize, or justify the abuse. "After every atrocity one can expect to hear the same predictable apologies: it never happened; the victim lies; the victim exaggerates; the victim brought it upon herself; and in any case it is time to forget the past and move on." (p. 8).

Herman's analysis suggests that the tendency to discredit and silence trauma victims is often intertwined with the misconception that their experiences are a manifestation of mental illness. This can take the form of dismissing trauma as delusion: when a survivor recounts a traumatic experience that seems unbelievable or challenges societal norms, their account may be dismissed as a delusion or hallucination, suggesting a psychotic disorder. The power dynamics inherent in trauma often allow the perpetrator's version of events to prevail, especially when the victim is already marginalized or devalued. "The more powerful the perpetrator," Herman writes, "the greater is his prerogative to name and define reality, and the more completely his arguments prevail." (Herman, 1992, p. 8) This can leave the victim feeling isolated and unheard, their experiences rendered unspeakable and their suffering invalidated. As Herman observes, "Without a supportive social environment, the bystander usually succumbs to the temptation to look the other way... When the victim is already devalued (a woman, a child), she may find that the most traumatic events of her life take place outside the realm of socially validated reality. Her experience becomes unspeakable." (p. 8).

This tendency to discredit and silence trauma victims is a recurring theme in the study of trauma. Herman notes the ongoing debate about the credibility of trauma survivors and the authenticity of their experiences, highlighting the persistent challenge of overcoming societal resistance to acknowledging the reality of trauma (Herman, 1992). This underscores the crucial importance of creating a social environment that supports and validates trauma survivors, allowing them to break the silence, reclaim their experiences, and begin the process of healing.

Rebuilding Trust: The Path to Healing from Trauma

Rebuilding trust is essential to the process of healing. Trauma can shatter an individual's trust in others, themselves, and the world around them. It is vital to create safe spaces where survivors feel validated and empowered, fostering an environment conducive to healing and growth. This involves not only individual support but also systemic changes that promote trauma-informed care in healthcare, education, social services, and the justice system.

Ultimately, healing from trauma requires a multifaceted approach that addresses both the individual and societal wounds. By understanding the complex dynamics of trauma, acknowledging the impact of disbelief and silence, and fostering environments that prioritize safety, trust, and empowerment, we can create a world where survivors are not only heard and believed but also supported on their journey toward recovery and wholeness.

Reference

Herman, J. L. (1992). Trauma and recovery: The aftermath of violence—from domestic abuse to political terror. Basic Books.